By Vanessa Brown

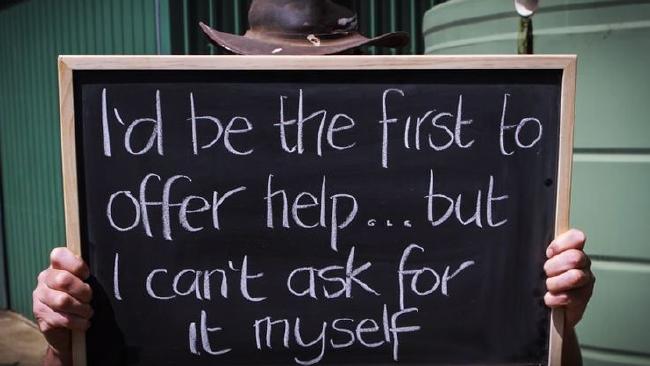

IT’S the side of farming that often goes unnoticed; the area we are still “too embarrassed to talk about”.

When Katrina was just 15-years-old, and her sister was 11, their “hardworking, outgoing and socially happy” dad took his own life on their farm in Barham, on the banks of the Murray River.

As a father and loving husband to their mother Debbie, Sandy Warne suffered years of depression while working as a farmer on his 800-acre avocado property.

“My grandparents brought the farm in the 70s, and then my dad took it on when they couldn’t run it any longer,” daughter Katrina, now 34, told news.com.au

“My dad loved the farm so much, and he wanted to be a farmer his whole life. While many farmers often don’t get off their property, dad was a huge community man, really involved in golf, tennis and squash. He was outgoing, happy and very social.”

While Sandy’s depression was “very well hidden from his friends and the local community”, his family was well aware of his spiralling condition — especially in the last six months of his life.

“Dad was just 42 years old when he died, and he kept what he was feeling very well hidden from those who weren’t family,” Katrina said.

“He was actually booked to go into hospital the day after he died, but I think the thought of doing that was just too hard for him.

“In the months before dad died, he lost a lot of weight. He was very stressed, because he and mum were considering selling the farm. It was meant to be sold a few days after he died because of financial reasons.

“Because of this reason, dad felt he was a failure. But according to mum, they were never in a position where they had to sell, I think dad just felt like the farm wasn’t going well enough, so he had to get rid of it.”

Katrina, who is now married and a mother to three young children, said her father’s dream to work the family farm with his brother’s played a big toll on his depression — because his fantasy never became a reality.

“He always wanted to run the farm with his family, his dad and brothers, but that didn’t happen and so that really affected dad. He couldn’t ever let go of that dream,” she said.

“In the later months, just before he took his life, my mum knew he was getting really bad. She and my uncle took the guns away from the house because he was potentially suicidal.

“We knew how sick he was, but the problem with mental health is that once they get to a certain point, it’s very hard to help them. For dad, going to the hospital the next day was just too hard.”

And that is one of the biggest problems Katrina, who is now involved with a Beyond Blue funded project called The Ripple Effect, says farmers face today.

“People, especially men, often try and hide a problem, and sometimes don’t even know how bad their mental state is until it’s too late,” she said.

“I’m very passionate about prevention, knowing what signs to look out for and what to do when you see them.

“People aren’t very good about asking if others are OK, but we really need to do it more, and be a little more paranoid about what is going on around us.”

While Katrina admits her father’s death didn’t have a huge affect on her life when it happened, she said his death impacted her more and more as she got older, because she had to explain the circumstances to new people.

“When dad died, mum explained things to me really well, and I felt I had an understanding with what had happened,” she said.

“When it happened, everyone at school knew what happened to my dad. But as I got older, no one knew the story, so I had to tell people. When I had kids, I found it even more difficult to talk about.

“With suicide no one wants to talk about it, you can almost feel embarrassed because you’re worried about another person’s reaction. My mum would never talk about it, and she still doesn’t.”

The most recent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Mortality Report shows that 15-24 year old males in regional areas are 1.5—1.8 times more likely to end their life by suicide than their urban counterparts. The incidence is up to six times higher in very remote areas.

In response to the dairy industry crisis, farmers in Queensland held a minute’s silence for those lost to suicide in the industry while rallying outside the state’s Parliament House.

“This is an industry-wide problem and when we’re talking industry-wide we are talking about everybody in this country,” Robbie Radel, a dairy farmer from Biggenden, said in an interview with the ABC.

“And while we’re thinking about everybody in this country I would ask you to take your hats off, we’re going to have a minute’s silence to honour those brave dairy farmers who couldn’t make their way out of this; they couldn’t see their way clear.

“They’ve taken their lives; they’ve taken what they believed to be the only option.”

Earlier this month, farmers across the Victoria were blindsided after the nation’s two largest processors, Murray Goulburn and Fonterra, slashed the price it pays suppliers for milk solids.

It’s raised new concerns about mental health and depression among dairy farmers.

Former Farmer Wants a Wife contestant Matt Goyder knows first hand what living on the land, combined with depression can do to a person. The 26-year-old, who is now an ambassador for Lifeline, has been suffering from mental health issues “since the age of 11 or 12”.

When he was 24, and six years into his career as a farmer in rural Western Australia, the cattle pastoralist spent five months in rehab to overcome his demons, and deal with post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I live, work and breathe next to the same people every day. It’s very hard to make friends, and it’s hard with relationships,” he told news.com.au

“You can’t speak to someone face-to-face about your feelings because you are so isolated. A lot of people don’t acknowledge there is a problem, because they think that being unhappy is normal.

“You get into a mentality that you don’t need friends, family or love, and you think the land and your working dog is enough. But everyone needs companionship.

“Going into rehabilitation at first was a terrifying experience, but I had reached a point where my favourite time of the day was bed, and my worst time was being awake.”

Mr Goyder, who now says he “is on top of the world”, blames the “alpha male mentality” as the reason for farming men in particular refusing to seek help for depression.

“No-one ever talks about their feelings on the land. Everyone has to hold this facade of being tough. Just grin and bare it,” he said.

“At the end of the day, everyone is human and we all have the right for love, sadness, passion and anger in life.

“There’s this culture in farming where men can’t express any of that, but they are actually really lonely. It’s such a slippery slope.

“These men dedicate their lives to a farm, so the idea that their work and their home can be snatched away because of debt … I can honestly see why people think there’s not another way out.”

The Ripple Effect, which will launch online next month, hopes to give a digital platform for farmers in rural communities who wish to express their experiences in an anonymous setting.

To read the full article: 2016-05-26: The heartwrenching reality of suicide and depression among Australian farmers – News.com.au